Introduction

Despite the delay in formalising the proposed Bilateral Trade Agreement (BTA) between India and the United States (US), India’s maritime operations in the Indian Ocean suggest that it will not minimise its policy priorities on strengthening ongoing military-to-military engagements between the two countries. Operational level interactions can build a strong steppingstone, generating maritime domain knowledge between militaries and supporting long-term defence diplomacy.

For example, a multi-mission maritime patrol and reconnaissance aircraft (MRPA) P-8A Poseidon from the Commander, Task Force (CTF) 72 (the United States (US)), joined hands with an Indian Navy MPRA P-8I, as part of a bilateral detachment that focused on anti submarine warfare (ASW) and Maritime Domain Awareness (MDA) in Diego Garcia and the Indian Ocean. The operational significance of this combined exercise between the Indian and the US Navy highlights the first time ‘the US and Indian crew [were working] together on operational planning for the exercises to set the groundwork for increased information sharing, and cooperation at sea.’

Great Power Cooperation for MDA

According to the International Maritime Organisation (IMO), MDA refers to having a comprehensive understanding of all factors related to the maritime domain that may affect the safety, security, and economic wellbeing of the marine environment. However, the vast ocean encompasses a multitude of activities that traverse several territories of the Indian Ocean, making information gathering and sharing a challenging task for any individual state. In fact, littoral states can, at best, acquire Maritime Situational Awareness (MSA), with real-time domain awareness being an aspiration for all.

Traditionally, Indian Ocean nations, including littoral states such as Sri Lanka, Maldives, and India, exchange information on maritime events, including illegal fishing, piracy, and distressed cargo vessels that cross their territorial waters. As a great power, India attains an inherent responsibility to secure the region, whilst also assisting its regional smaller states to strengthen their maritime security capabilities. Smaller nations will always have limitations in gathering and sharing information about threats arising at sea at the regional scale.

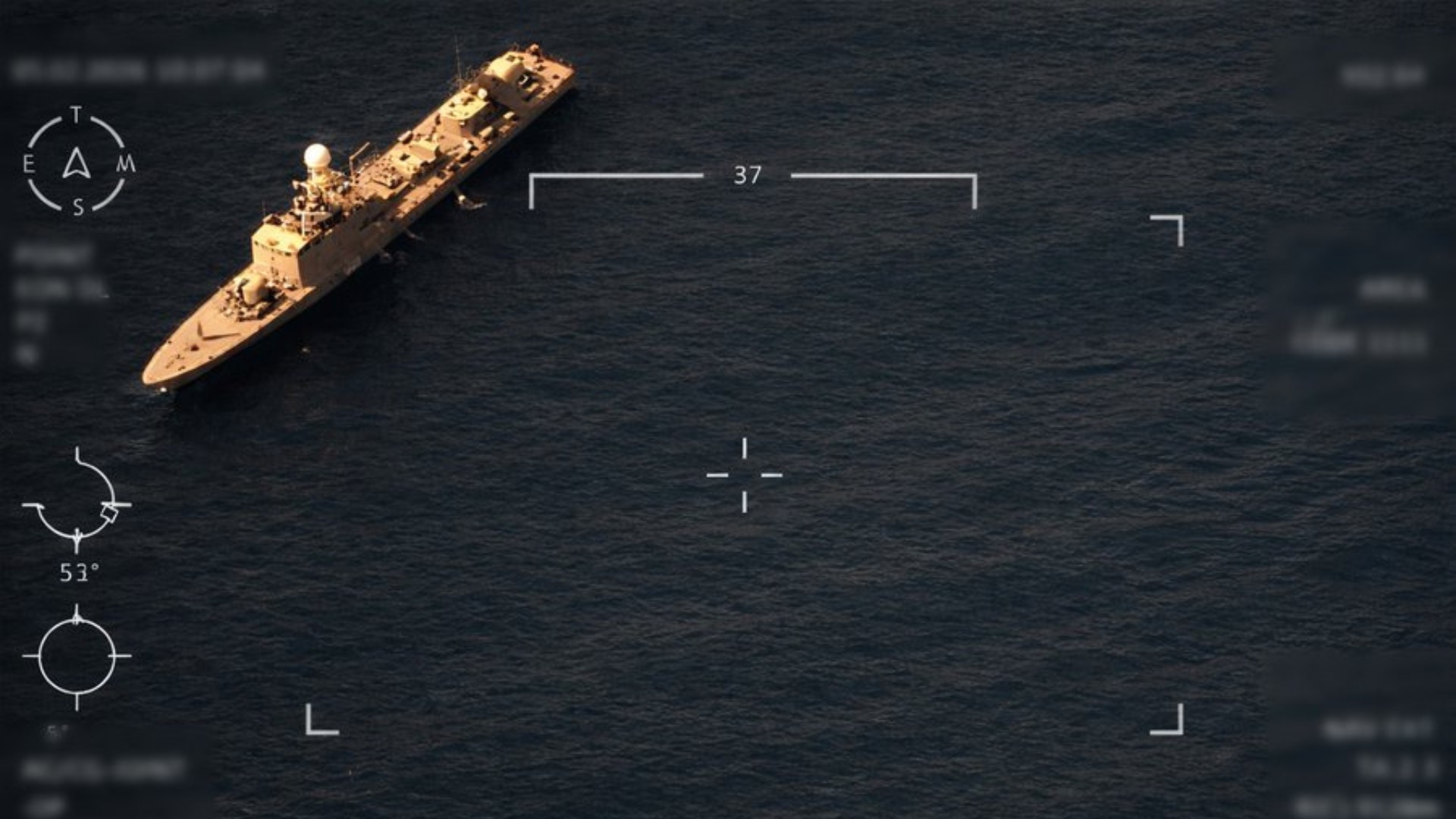

This is where India and the US have an opportunity to step up to strengthen regional frameworks, including the governance of maritime domain operations, to curb the potential rise of single powers that can undermine the regional rules-based order. The US-India collaboration can improve MDA capabilities in this respect and has been supported by the incorporation of surveillance systems, radar networks and Unmanned Aerial Vessels (UAVs).

The Indian Ocean Region has also suffered from existential ‘sea blindness’. Hence, cooperation between India and the US can enhance bilateral MDA capabilities and support regional organisations such as the Indian Ocean Rim Association (IORA) and the Colombo Security Conclave (CSC), strengthening shared identities in a free and open Indo-Pacific.

The US-India MDA and Interoperability

India and the US can strengthen their maritime security partnership by formulating a comprehensive strategy to track Chinese submersibles in the Indian Ocean. India can leverage the existing ‘US-Japan fish hook’ sound surveillance system. The Fish Hook Undersea Defence Line, since 2005, stretches from Japan to East Asia, with key nodes in Okinawa and Taiwan. It consists of two separate networks of hydrophones, one stretching from Okinawa to Kyushu and another from Okinawa to Taiwan. Moreover, seabed sensors may be required to monitor Chinese submarines entering the Indian Ocean.

India and the US could directly attempt to address the issues associated with the Chinese maritime militia fleet, colloquially known as the “little blue men”. While the India-US February 2025 joint statement has so far focused on improving maritime interoperability, it has shied away from addressing the imminent threat caused by the maritime militia directly.

It is equally important to leverage the existing foundational agreements, such as Communications Compatibility and Security Agreement (COMCASA). Since India now has access to Combined Enterprise Regional Information Exchange System (CENTRIX) terminals, it could use them more frequently on its platforms and not just during combined exercises. This will enable genuine integration of such platforms and improve interoperability.

India’s Collective Efforts

India can also continue to build its own capabilities, such as its own software systems, including the Network for Information Sharing (NISHAR-MITRA), under the aegis of different Indian agencies. Combine its leadership with its US partnership. For example, India is likely to purchase the SeaVision software from the US HawkEye 360. It can share this software with other neighbouring countries, such Maldives and Sri Lanka, so that one can have access to a more nuanced common operating picture (COP) of the Indian Ocean Region.

For small states with big ocean territories, MDA, in the words of a leading author, ‘is not a mere technical capability but a strategic necessity’. By sharing existing technologies, such as NISHAR-MITRA and SeaVision, India can reinforce its position as the platform for regional security engagements supporting MDA. For example, Maldives relies on regional cooperation to curb and manage threats arising at sea. India is an integral part of the maritime security operations of the Maldives and enables the latter to address its maritime security challenges, with Exercise Dosti being a conduit in the process.

India, under the aegis of the Information Fusion Centre in the Indian Ocean Region (IFC-IOR) can collaborate further with the Information Fusion Centre in Colombo. India can also cooperate with Maldives and assist the latter in setting up its own IFC. These IFCs and other maritime rescue coordinating centres constitute critical maritime infrastructure due to their role as data/information collection and diffusion centres, and such direct assistance on India’s part to Maldives and Sri Lanka can foster a spirit of long-term collaboration among the littoral states.

India can also leverage its existing White Shipping Information Exchange (WSIE) Agreements with the littoral states. India, Maldives and Sri Lanka already share unclassified information on white shipping over the Merchant Ship Identification System (MSIS) format. Similarly, India can utilise its Maritime Information Sharing Technical Agreement (MISTA) with the US, ‘to facilitate identification of dark shipping through innovative means and progressively share such information with partners’.

In collaboration with India, the US can also leverage existing multilateral groupings to support Indian efforts in the Indian Ocean. Through the Indian Ocean Rim Association (IORA), where the US is a dialogue partner, and the Colombo Security Conclave (CSC), which is the most active security grouping. With the Indo-Pacific Maritime Domain Awareness (IPMDA) and the Maritime Initiative for Training in the Indo-Pacific (MAITRI), both India and the US can collaborate to ensure better critical regional coordination in the region.

Such engagements could enable the US to engage with the Western Indian Ocean Region, where it has limited presence, with India, the US and other littoral partners benefiting from such efforts. An obvious example could include sustaining the US participation in the Maritime Information Sharing Workshops and other Table-Top Exercises conducted by the IFC-IOR and the Indian Navy.

Conclusion: India’s leadership in regional security

While India and the US cooperation on MDA can strengthen the rules-based international order, it can also enable India to proactively harness holistic maritime security for the region. At a time when India’s Indo-Pacific identity has taken centre stage, Indian support to the IOR states could be a win-win for the country, enabling India to reinforce its position as the ‘preferred security partner’ in the Indian Ocean Region. It could also enable India to better manage non-traditional security threats that have come to plague the region.

MDA tools and assets constitute a ‘collective public good’ that can ensure a safe and secure maritime environment for all littoral states. Since India is at the helm of affairs in the Indian Ocean Region, it must reinforce its commitment to build a secure, resilient and cooperative future for the region. This renewed assurance on India’s part will ensure collective maritime security preparedness for all littoral states. In this regard, the construction and maintenance of MDA tools and assets could be a key prerequisite, and India, along with the US, must take the lead to make this a reality.

Author

Anuttama Banerji is a Research Associate at the National Maritime Foundation, New Delhi, India. She graduated with a Master’s degree in International Relations from the London School of Economics and Political Science (LSE) in 2018. The author acknowledges that statements, opinions and arguments made are of her own and do not reflect the Indian Government’s policies and positions.