By Shimna Shakeeb

Technology integration is a key characteristics of modern higher education delivery and even the most traditional universities are following the emerging trend. Therefore, it is not surprising to see rapid adoption of technology in teaching and learning in higher education offerings in the Maldives too. One has to accept that there is no escape from this evolving trend. It is also important to be aware of the prevailing perceptions of online education as a poor, cheap, low quality option and how this view continue to be a part of the dialogue related to the quality of online education. Consequently, it is not surprising to observe a strong resistance to online education from people from the academia as well as society at large. What is missing is and urgently required in the current context in the Maldives is a robust and transparent external and internal quality assurance process which can be applied for online education design and delivery to ensure both effective delivery and to garner support for online education.

Arguably, quality assurance of online education is one of the many challenges universities across the globe has to tackle with (Marciniak, 2018). In the case of Maldives, at present, online education is offered in the absence of a national quality assurance framework for technology integrated learning. Thus, institutions are not required to comply to a legal national online education framework or standards. In addition, criteria and indicators set for the evaluation of traditional programs are applied to assess the quality of e-learning programmes or programs with a significant online component. This indicates that quality dimensions and indicators appropriate to the context of e-learning is not applied in the quality assurance process. In addition, Maldives accreditation agency applies the same processes/models applied to traditional education programmes to assess and certify technology integrated/virtual programmes as well. This can be a major quality setback for institutions offering or intending to offer e- courses as online education differs from conventional education when it comes to how it is structured and delivered. Therefore, it is critical at this stage to integrate e–learning quality criteria and standards in both the national higher education quality assurance framework/system and the internal quality assurance mechanisms applied by individual tertiary level institutions. Taming the rapidly growing online education adoption is critical during the early stage before poor quality online education delivery models becomes normalized. If left untamed, the application of unpredictable ‘wild teaching and learning models’ can have serious irreversible quality consequences. In this regard, the absence of online quality standards and frameworks is problematic and hence, should be a major concern for all involved. This article is stimulated by some of the debates and concerns around the current online education delivery in tertiary level in the Maldives. It serves as a thought-provoking stimulant for online education administrators and educators engaged in formulating quality program goals and assessment policies for e-learning programs.

What does quality assurance of online education mean?

In an article published in 1985, which is now commonly cited, Christopher Ball asked, “What the hell is quality?” Thirty-five years later higher education institutions are still grappling with this question. Hence it is not surprising to note that there is no one agreed definition of quality in higher education. A commonly cited definition of quality comes from Harvey and Green (1993) who defined quality assurance as the methods employed for checking the quality of processes or outcomes. Many have also argued and proposed quality as a multidimensional concept with multiple and interrelated meanings which can be differentiated but not completely disconnected from each other (Harvey and Green 1993; Westerheijden, Stensaker and Rosa 2007; Kleijnen et al. 2013).

Over the last decade, perceptions about the quality of online learning have shifted in many countries. A number of quality standards have been identified, proposed and published as well. For example, the Sloan-C Framework identified the following five aspects; (1) learning effectiveness, (2) access, (3) student satisfaction, (4) faculty satisfaction, and (5) cost effectiveness as the five pillars of quality (Lorenzo & Moore, 2002). Similarly, Barnard and Echols (2015) and Rushby and Surry (2016) proposed that an online education programme should focus on clarifying and developing the following nine components; (1) Online programme justification (What is the reason for the existence of the online education programme?), (2) Online programme objectives (What is the online education programme for?); Student profile (Who is the online education programme for?); (3) Thematic contents (What is going to be taught?), (4) Learning activities (How is the online education programme going to be carried out?), (5) Online teacher profile (Who is going to conduct the online education programme?), (6) Didactic materials and resources (What is the online education programme going to be carried out with?), (7) Learning assessment strategies (How is the student’s learning process going to be assessed), (8)Tutorial (What support is going to be offered to the students during the learning process?) and (9) Virtual classroom of the programme (What is the virtual environment of the programme going to be like?). According to Bates, (2015), the best guarantees of quality in teaching and learning fit for a digital age are; (1) well-qualified subject experts also well trained in both teaching methods and the use of technology for teaching, (2) highly qualified and professional learning technology support staff (3) adequate resources, including appropriate teacher/student ratios, (4) appropriate methods of working (teamwork, project management), (5) systematic evaluation leading to continuous improvement. Furthermore, Online learning Consortium (2016) identified the following nine elements as critical benchmarks for successful online education.

Figure 1: Quality elements proposed by Online learning Consortium Scorecard for online courses (2016)

In the absence of a national online education standards, establishing strong internal quality assurance processes within individual higher education institution becomes particularly important. The widespread growth of online education by higher education institutions in the Maldives necessitates the adoption of online education quality assurance frameworks which can be used at institutional level. Quality assurance starts with adherence to a set of standards identified by research and informed by best practices. In this regard, there are several online education quality assurance standards/frameworks which can be used for quality assurance purposes. Pedro & Kumar (2020) discussed thirteen such online education quality assurance frameworks in their study. Strengthening internal quality assurance through the application of international best practices and benchmarks can provide quality assurance of online courses and help institutions to shift towards a culture of quality.

Quality Matters (QM) Quality Assurance process

Quality Matters (QM) is a quality assurance process used extensively across higher education institutions. QM quality assurance process offers a simple framework to ensure quality of online ,hybrid and Face-to- Face courses. The proposed standards in QM are supported by literature reviews of online learning research and best practices observed from best performing institutions. QM offers a Course Design standards Rubric which highlights 8 general standards and 42 specific review standards which can be used to evaluate the course design of online and blended courses. The rubric has a 3-point scale system that can be used to score each specific standard.

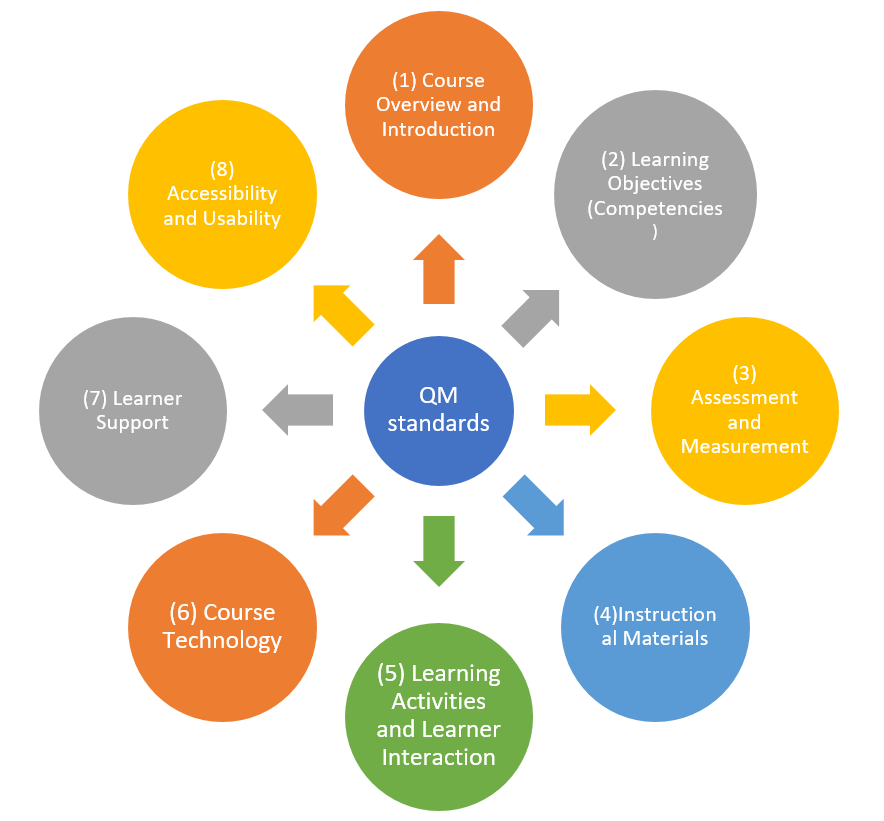

The QM eight general standards (see Figure 2) is based on sound conclusions gained from the educational research literature regarding factors that contribute to the improvement of student learning and retention rates, and activities that support the enhancement of student engagement and learning. It is important to note that institutions can opt for QM- certified online or blended courses by meeting the QM standards through an official review.

Figure 2: Quality Matter standards within the QM framework

QM rubric can be applied to different delivery modes (see table 1) including online, blended and Face-to-Face. The first step towards quality assurance is to apply the QM rubric during the course design process. If traditional courses are converted to online or hybrid courses, it is important to redesign the courses and align the components to the standards specified in the QM rubric. The second step is to apply QM rubric to evaluate online and hybrid courses which are currently offered by the institutions. Therefore, it is important for universities and colleges to prioritize the training of different stakeholder such as individual faculty and instructional designers to apply the QM standards in course design and course evaluation.

| DELIVERY MODE | DESCRIPTION | INSTRUCTION | APPLICATION OF QM RUBRIC |

| Online | 100% of the content and instruction is mediated by technology. | All instruction occurs online within a course site, typically hosted in a learning management system (LMS). HE: Few to no face-to-face meetings | Online courses can become QM-Certified with the respective QM Rubrics and QM course review process. |

| Blended | Approximately 25-75% of the course takes place in a face-to-face environment. Seat time is reduced proportionately to the percentage of the course delivered online. | The integration of both F2F and online activities occurs in a blended course. Portions of the course are mediated by technology. Learners can gain an understanding of the overall structure and requirements of the course online. | The QM Rubric is applied to the online portion of the course. F2F components of the course are not directly reviewed. Only content, instructional materials, activities, support materials, etc., included or referenced in the online course are considered in the QM review. |

| Face-to-Face (F2F) | 100% of the course occurs in regularly scheduled sessions where learners meet in person at a campus location with their instructor on a regular basis. The course may include use of a learning management system and extensive internet-based reading/research assignments and online discussions. | Syllabus, readings, assignments, and grade book may be in the LMS, however, the course is conducted in regularly scheduled F2F meetings on campus. | While principles of the QM Rubric Standards can be applied to F2F courses, due to the nature of the course review, it is not possible to have F2F courses QM-Certified. |

Table 1: Type of courses to which QM rubric can be applied

Supporting innovation and change is important for the modernization of higher education delivery in the Maldives. Quality assurance of online education is a concern in the Maldives and it has to be addressed urgently in order to ensure that the rapidly growing technology integrated programmes are design and delivery process follow best online learning standards and practices. There are a several quality assurance frameworks which can be contextualised and adopted for quality assurance purposed of online/hybrid courses offered by tertiary education institutions.

Reference

Marciniak, R. (2018). Quality assurance for online higher education programmes: Design and validation of an integrative assessment model applicable to Spanish universities. International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 19(2)

Harvey, L., & Green, D. (1993). Defining quality. Assessment & evaluation in higher education, 18(1), 9-34.

Kleijnen, J., Dolmans, D., Willems, J., & Hout, H. V. (2013). Teachers’ conceptions of quality and organisational values in higher education: compliance or enhancement?. Assessment & Evaluation in higher education, 38(2), 152-166.

Westerheijden, D. F., Stensaker, B., & Rosa, M. J. (Eds.). (2007). Quality assurance in higher education: Trends in regulation, translation and transformation (Vol. 20). Springer Science & Business Media.

Green, D. (1994). What Is Quality in Higher Education?. Taylor & Francis, 1900 Frost Road, Bristol, PA 19007-1598.

Pedro, N. S., & Kumar, S. (2020). Institutional Support for Online Teaching in Quality Assurance Frameworks. Online Learning, 24(3).

Lorenzo, G., & Moore, J. (2002). The Sloan Consortium report to the nation: Five pillars of quality online education. Retrieved February, 21, 2008.

Barnard, D., & Echols, J. (2015). The anatomy of K-12 online programs: Practical ideas and guidelines. London: Rowman and Littlefield.

Rushby, N., & Surry, D. (2016). Wiley handbook of learning technology. New York: John Wiley and Sons.

Bates, A. T. (2018). Teaching in a digital age: Guidelines for designing teaching and learning.

Online Learning Consortium. (2016). Quality scorecard for the administration of online programs